By Paul Ivsin, Executive Vice President, Analytics, Insights, and Media

If there is one thing we can agree on, it’s that informed consent forms (ICFs) for clinical trials are just not patient friendly.

The most obvious problem is length. Recent phase 3 ICFs we’ve seen have ranged from 30 to over 40 pages, with many topping out over 20,000 words in length. (To put that in perspective – an audio recording of a 20,000-word document would run for about two hours!)

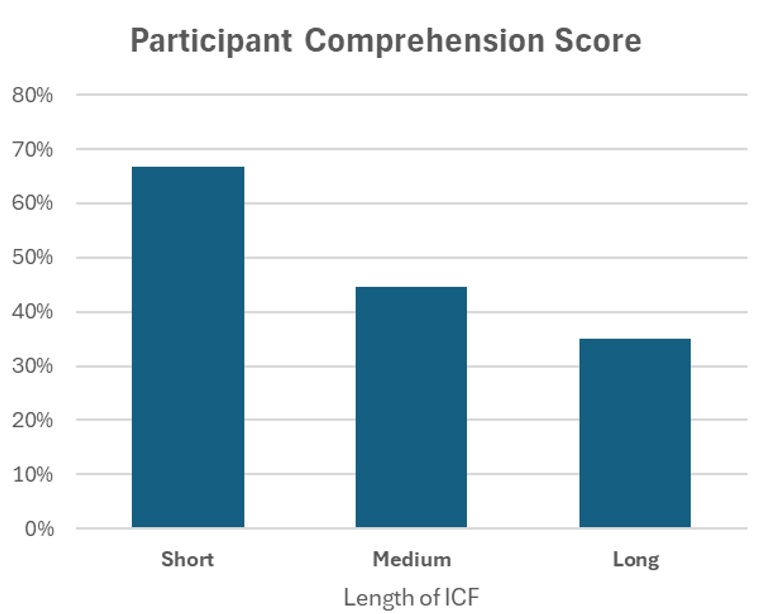

This is not a new concern. Over 50 years ago, Lynn Epstein and Louis Lasagna conducted a small but powerful study showing that participant understanding of the study got progressively worse as the length of the ICF increased. Since then, a large volume of research on information processing and cognitive load has made it painfully clear that simply piling on more information does not make a person more informed.

The problem is that while we can all agree that there’s an overwhelming amount of information in the ICF, there is no consensus on how to make it shorter. Every required element in the ICF might be a critical factor in a participant’s decision, so regulators and IRB reviewers balk at the idea that there might be benefit in paring the form down.

In fact, in last year’s final guidance, FDA actually added 4 new elements to the ICF. As research evolves over time, new concerns arise (for example, the potential use of Whole Genome Sequencing data) and naturally, we need to load more things in without removing anything else in the process.

So, if our ICFs are doomed to always expand, what can we do?

The NIH and FDA have struck on a new solution to this decades-old problem: they want ICFs to get even bigger.

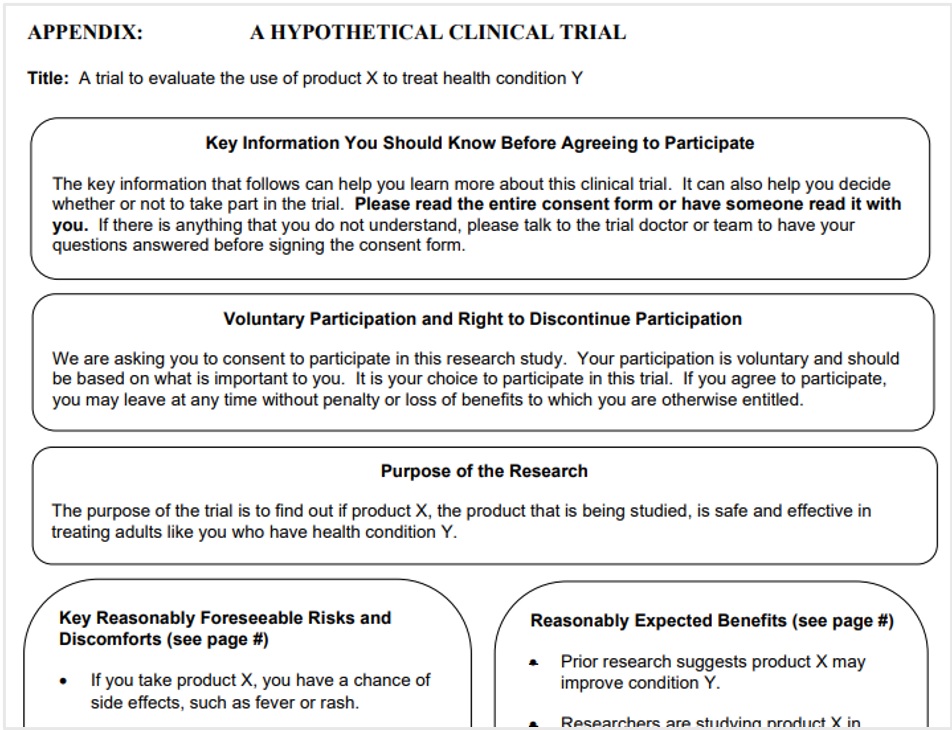

Specifically, FDA’s guidance last month calls for a new section at the beginning of the ICF: Key Information. The Key Information section is not intended to replace the full text of the ICF but will call out important points at the beginning.

The guidance does not use the phrase “executive summary”, but that’s a reasonable analogy here. If you produce a document with so much detail that it’s bound to overwhelm your readers, then providing a quick synopsis at the beginning seems helpful and considerate. We may find that a smart summary actually manages to improve reading comprehension and provides a better experience for trial enrollees over time.

That is certainly NIH and FDA’s hope with the new section – the guidance even includes a couple pages dedicated to a discussion of how to improve understanding of the ICF, and the issue is clearly on FDA’s mind (see pictured example of FDA’s use of “bubbles” to highlight content).

But there is still good reason to be concerned that these latest changes will exacerbate, rather than solve, our challenges with informed consent. It’s worth noting that the sample Key Information section that FDA provides contains a whopping 10 sections of information. And really, that’s not a surprise: the same pressure to add information to the ICF will almost certainly also come to bear on the Key Information. If everything is important, then IRBs will of course want to see that highlighted in the Key Information – and may push back if the Key Information section is too concise.

It’s possible that the Key Information section will end up being a valuable new part of the consent process, but our recommendation is that patient engagement is best achieved through thoughtful pre- and post- consent communication tools, including

- Personalized conversations through secondary prescreening calls and/or patient navigators

- Short, relevant content such as intro videos

- Open ended site/patient discussion guides

Ultimately, the goal is for us to understand what information each patient considers key, and deliver that to them in the clearest, easiest manner possible. To learn more about how we achieve this goal in our programs, please contact us to continue the conversation!